WASHINGTON – Jan. 7, 2022 – Quillette — Washington, DC

A review of The Age of AI and Our Human Future by Henry A. Kissinger, Eric Schmidt, and Daniel Huttenlocher. Little, Brown and Company, 272 pages (November, 2021).

Potential bridges across the menacing chasm of incompatible ideas are being demolished by a generation of wannabe autocrats presenting alternative facts as objective knowledge. This is not new. The twist is that modern network-delivery platforms can insert, at scale, absurd information into national discourse. In fact, sovereign countries intent on political mischief and social disruption already do this to their adversaries by manipulating the stories they see on the Internet.

About half the country gets its news from social media. These digital platforms dynamically tune the content they suggest according to age, gender, race, geography, family status, income, purchase history, and, of course, user clicks and cliques. We know that their algorithms demote and promote perspectives that may come from opposing viewpoints and amplify like-minded “us-against-them” stories, further exacerbating emotional response on their websites and in the real world. Even long-established and once-reputable outlets capture attention by manufactured outrage and fabricated scandal. Advertising revenue pays for it all, but the real products here are the hundreds of millions of users who think they are getting a free service. Their profiles are sold by marketeers to the highest corporate bidder.

In her book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Shoshana Zuboff meticulously describes how our online behavior and demographic data are silently extracted and monitored for no greater purpose than selling us more stuff. She quotes UC Berkeley Emeritus Professor and Google’s Chief Economist Hal Varian, who explains how computer-mediated transactions “facilitate data extraction and analysis” and customize user experiences. Google, the market leader in online advertising for over a decade, has benefited most of all. Their third quarter revenue in 2021 for advertising alone was up 43 percent (compared to the same period in 2020) to $53 billion. The models and algorithms work.

Let’s leave aside for a moment the moral and ethical considerations of data rendition that internet properties use to collect information, and focus instead on what they do with it. This brings us to the epistemic threshold of artificial intelligence and machine learning, or “AI and ML.” In their new book, The Age of AI and Our Human Future, Henry Kissinger (Richard Nixon’s Secretary of State), Eric Schmidt (the former chair and CEO of Google), and Daniel Huttenlocher (the current and inaugural dean of the Schwarzman College of Computing at MIT) sound the alarm about the technological dangers and philosophical pitfalls of uncontrolled and unregulated AI. They join an august list of technology luminaries and public intellectuals who have expressed similar concerns, including Stephen Hawking, Sam Harris, Nick Bostrom, Ray Kurzweil, and Elon Musk.

Their persuasive arguments are brilliantly cast in the sweep of historical context and implicitly coupled to their global reputations. According to Kissinger, Schmidt, and Huttenlocher (KSH), only with official government oversight and enforceable multilateral agreement can we avoid an apocalyptic future that subordinates humanity to (mis)anthropic computers and robots. They cast some of AI’s early results as the first step on the alluring-but-broken pavement to cyborg perdition. They urgently recommend international negotiations comparable in diplomatic and moral complexity to cold war nuclear-weapon treaties. And I believe that they are mistaken in perspective and tone.

The fundamental principle upon which I base my counter-argument is that, as Erik J. Larson explains in The Myth of Artificial Intelligence, “Machine learning systems are [just] sophisticated counting machines.” The underlying math is inherently retrospective and can only create statistical models of behavior. Curiously, this is a derivative insight of Varian’s paper; winning platforms have insurmountable advantages because they have the most users, which makes them attractive to more users. As long as there are no material outliers in the data, their stochastic distributions can be, as compactly stated by the OED, “analyzed statistically but not predicted precisely.”

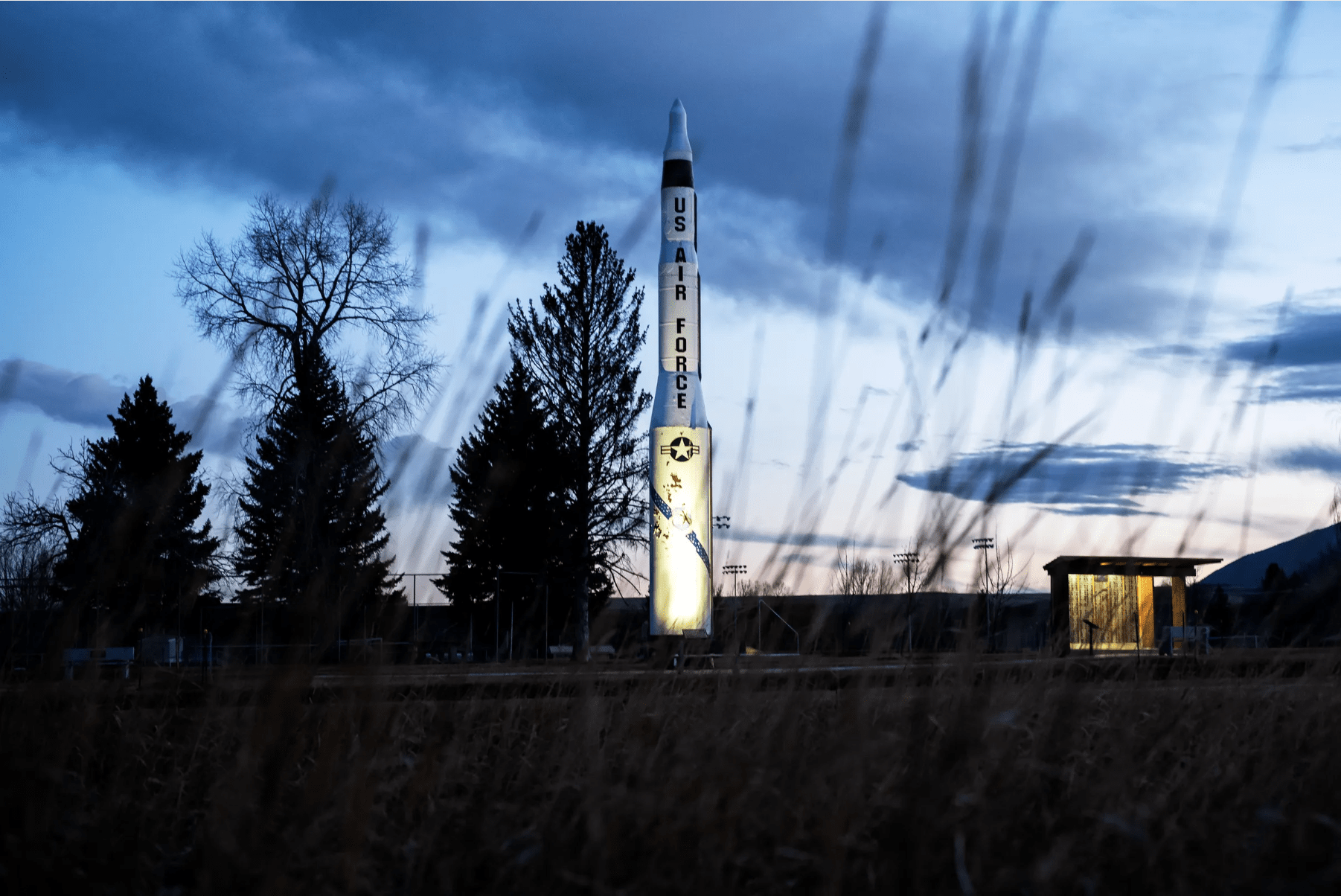

Of course, the algorithms are brilliant, the insights sublime. The number of behavioral and demographic attributes that network platforms collect and correlate is a secret (this itself is a topic of contention), but it is probably in the hundreds or thousands. But whatever magic there is exists in the underlying platforms and their attached memory, not in some latent superhuman insight that should invite concerns about autonomously directed objectives, never mind cyberdreams that threaten our survival. (We have much bigger problems than that today: climate change, social unrest, religious zealots with strategic weapons, to name three.)

A trite-but-revealing counterexample is sometimes referred to as Russell’s Turkey, after one of the most influential logicians of the last century. In formal terms, it demonstrates the inherent limits of inductive inference, which basically says, “just because it’s happened a lot, doesn’t mean that there’s an undiscovered law of nature that says it will keep happening.” A turkey may conclude that it will be fed every day because that is what happens until it is slaughtered just before Christmas or Thanksgiving. The outlier can make all the difference. Ostensibly rare events—which in the real world are not-so-rare—are explored in Nassim Taleb’s iconic book, The Black Swan.

Larson’s and Taleb’s identical punchline is that any inductive model will look good for a while, right up until something is different: a so-called fat tail distribution. AI and ML models are inherently inductive—all their “predictions” are based on the past—and therefore can be deceptively incorrect at the moment it matters most. That’s okay for Google (another ad awaits!) but it is not okay for autonomous weapons systems, because the mistakes are irreversible and, using Taleb’s definition of fat tails, “carry a massive impact.” Kinetic decisions cannot be undone.

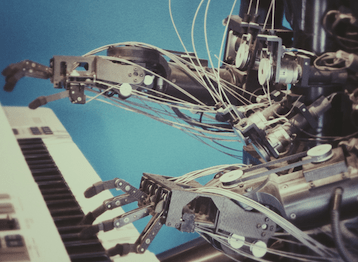

KSH understand this, of course, but they conflate the “ineffable logic” of AI with “[not] understanding precisely how or why it is working” at any given moment. Indeed, on the same page, they go on to say that “we are integrating nonhuman intelligence into the basic fabric of human activity.” Belief in non-human intelligence is akin to other kinds of human convictions that may feel correct but lack objective evidence. Automated pattern-matching and expert digital systems lack emotion, volition, and integrated judgement. I am not ruling out the possibility of a machine replicating these human-like features some day, but today that question is philosophical, not scientific.

Some computers take action or make decisions based on sensory inputs, yes, but they are no more intelligent than a programmable coffee pot. Cockpit instruments, for example, do more than boil water on a timer—dog-fighting jets are at the other end of the competency spectrum—because a team of humans designed and built them to perform more complicated tasks. In the case of a coffee pot we know precisely how and why it is working; in the case of a cockpit (or a generative speech synthesizer), the number of possible decisions is larger and their impact more important, but both are still constrained. It cannot do surgery. It lacks moral reflection.

KSH emphasize that AI can play better chess than any human ever has; has discovered a medicine no human ever thought of; and can even generate text able to “unveil previously imperceptible but potentially vital aspects of reality.” But these are just systematic and exhaustive explorations of kaleidoscopic possibilities with data that was provided, and rules that were defined, by humans. AI systems can check combinations (really, sequences) of steps and ideas that no human had previously considered. KSH, however, connect these astonishing technical achievements to “ways of knowing that are not available to human consciousness,” and call upon Nobel laureate Frank Wilczek’s Fundamentals for support:

The abilities of our machines to carry lengthy yet accurate calculations, to store massive amounts of information, and to learn by doing at an extremely fast pace are already opening up qualitatively new paths towards understanding. They will move the frontier of knowledge in directions, and arrive at places, that unaided human brains can’t go. Aided brains, of course, can help in the exploration.

On this point we can all agree. But then Wilczek goes on to say, indeed in the very next paragraph, that:

A special quality of humans, not shared by evolution or, as yet, by machines, is our ability to recognize gaps in our understanding and to take joy in the process of filling them in. It is a beautiful thing to experience the mysterious, and powerful, too.

This is the philosophical crux of the counter-argument. If we thought at gigahertz clock speeds, and were not distracted or biologically needy, we could get there too. That AI finds new pathways to success in old games, modern medicine, creative arts, or war that we might never have considered is magnificent, but it is not mystical. (My company does similar things today for claims adjudication and cybersecurity infrastructure.) No amount of speed, or data, or even alternative inference frameworks, will enable a machine to conceive an authentically new science or technology; they can only improve the science and technology we already have.

Indeed, that same class of backward-looking event-counting algorithm might deliver a dangerous answer fast in exactly the moment when a slow, deliberative, and intuitive process would serve our security interests better. The book might have included an example of how just one person, Stanislav Petrov, averted a nuclear holocaust by overriding a machine recommendation with human judgment in a situation neither had seen before—the very definition of an outlier. The Vincennes tragedy, where an ascending Iranian civilian airliner was mistakenly tagged as a descending F14 “based on erroneous information in a moment of combat stress and perceived lethal attack,” also deserves mention; over-reliance on a machine cost hundreds of lives. Neither incident would have benefited from “better AI.”

This is where KSH and their cohort philosophically misalign to the fundamental limits of inference engines. Some of the technical impediments to artificial general intelligence are insurmountable today, while others remain demonstrably out of reach. The fear, or hope, is that one day we will break through these barriers to deeper understanding of intelligence, sentience, consciousness, and morality, and then we will be able to reduce these insights to code. But there is no reason to believe we are anywhere near such a breakthrough. Indeed, what we do understand indicates, because of how logical propositions are expressed and interpreted, that the goal is impossible. For example, as Larson summarized:

[Kurt] Gödel showed unmistakably that mathematics—all of mathematics with certain straightforward assumptions—is strictly speaking, not mechanical or “formalizable.” [He] proved that there must exist some statements in any formal (mathematical or computational) system that are True, with capital-T standing, yet not provable in the system itself using any of its rules. The True statement can be recognized by a human mind, but is (provably) not provable by the system it’s formulated in.

[Mathematicians thought] that machines could crank out all truths in different mathematical systems by simply applying the rules correctly. It’s a beautiful idea. It’s just not true.

In other words, there are ideas that no machine will ever find, even if we do not yet fully understand why humans can and sometimes do. The best argument that KSH can make in riposte is that even if there is a small chance of conceptual extension, we should take care to (and invest resources into) neutralizing it now, before it is too late. But this is worse than implausible, it is unnecessary. The talent and training we need to address existential threats are already inadequate; to add yet more burden would misallocate the real intelligence we do have to the wrong class of problem.

AI only knows what is in the data. The unfortunate use of the term “learning” is a simple, but potent, source of confusion and apprehension. These machines are nothing more than wonderfully sophisticated calculators, even the ones that sound human (and pass the so-called Turing test) or can generate fake videos that an ordinary person would believe is real. Today, they are incapable of discovering fundamentally new facts (chess moves don’t count), or assigning new objectives (nor does protein folding), other than what is contained in the data they consume or the probabilistic rules they follow that are, by definition, consistent but not complete. There are some true things AI will never see without a lot of help.

I acknowledge that there are deep and legitimate concerns about the freedom-limiting dystopia we create by ubiquitous sensors, website trackers, and behavioral analytics. There is nothing particularly magnificent about the hatred and violence induced by AI-enabled social media platforms designed to produce addictive behavior, narrow users’ perspectives, and irretrievably sharpen convictions. Indeed, all three of the authors established their reputations by assembling as much data as possible to predict human behavior. Their sincere concern about technological overreach and privacy intrusion, from point assembly to coercive control, is justified.

But to allow Alan Turing to establish the standard of artificial intelligence is like allowing Thomas Jefferson to establish the standard of political liberty. These men made spectacular contributions to our scientific understanding and our social compact, respectively; one held AI intuitions that have since been proven wrong, the other held slaves. Does that diminish their genius? Of course not. But the comparison is apt, and their mortal discourse is subject to immortal debate that, as far as we can see today, no machine will understand, unravel, or replicate.